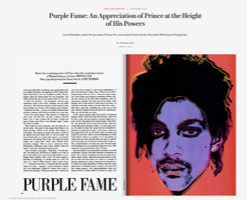

In 1981, photographer Lynn Goldsmith took a series of studio photographs of Prince on assignment from Newsweek, including this one. The assignment was cut short when Prince became uncomfortable and left, and the photo was never published.

When I give presentations to visual artists about copyright, by far the most common questions are about photographs. Visual artists often use other people’s photographs as the basis for their works. I explain that copyright protects only creative expression and not facts or ideas behind that expression, but also that photographs, which could be seen as records of existing factual realities, are nevertheless protected by copyright. Visual artists can therefore risk copyright infringement when they copy photographs.

But what about Andy Warhol? I am often asked: If he could do it, why can’t I? The short answer has always been: several photographers alleged copyright infringement claims against Warhol, but all of those cases settled. We didn’t know if courts would’ve decided that his works were infringing.

Until now. A new court case has found that at least some of Warhol’s works infringe the photograph he used to create them.

Copyright in photographs doesn’t give the photographer a monopoly on the subject matter, but it does protect the photographer’s artistic choices. For studio and staged photography, such choices are obvious: the photographer often chooses the set, props, wardrobe, posing and lighting of the subject. But even photos taken on site, such as by sports photographers or photojournalists, are protected. Copyright protects the photographer’s artistic decisions as to the angle and point of view, composition, selection of camera and film (or digital settings), exposure, and capturing the particular lighting, action or expression of her subject at the moment in time when she takes the shot.

Generally, if you copy these aspects of a photograph, you will be liable for infringement, even if you’ve added a lot of your own artistic expression (such as an illustration based on a photo, or a digitally manipulated photo).

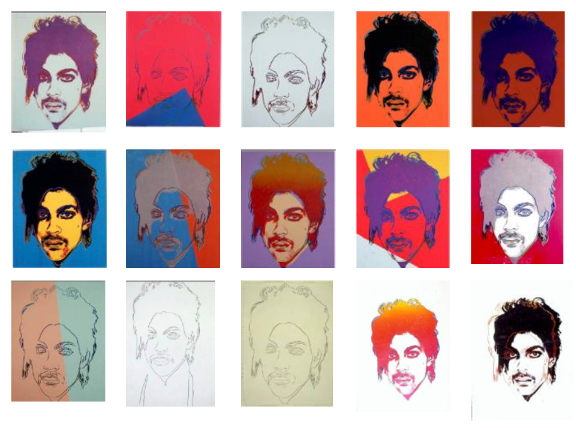

Earlier this year, the Second Circuit (federal appeals court) in New York decided that Warhol’s series of 15 images based on a photograph of Prince are infringements. The court rejected arguments that his works are fair use. In this context, fair use is a defense to infringement that will excuse unauthorized copying if the new artwork is sufficiently “transformative” – a concept that is unfortunately extremely unclear in the case law.

According to this new court decision, Warhol’s images (or at least the ones at issue in that case) copied too much of the artistic expression of the photograph they were based on. The extra artistic expression he added himself – which the court described as “removing certain elements from the [photograph], such as depth and contrast, and embellishing the flattened images with loud, unnatural colors” was not enough to make his works transformative.

The trajectory of this case illustrates how thorny the infringement vs. transformative fair use issue can be.

In 1981, photographer Lynn Goldsmith took a series of studio photographs of Prince on assignment from Newsweek, including this one. The assignment was cut short when Prince became uncomfortable and left, and the photo was never published.

In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed Goldsmith’s photo to be used as an artist’s reference for an illustration of Prince. Goldsmith was not aware that the artist would be Warhol. Vanity Fair published Warhol’s illustration to accompany its article, Purple Fame, with attribution to Goldsmith as well as Warhol:

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, however, Warhol went on to create a series of 15 additional images from her photo:

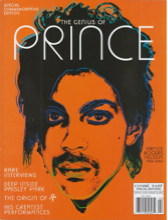

When Prince died in 2016, Condé Nast licensed one of those extra images from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the cover of its tribute magazine The Genius of Prince. Unlike the earlier publication in Vanity Fair, Goldsmith was not given credit for the image, which was instead attributed solely to the Andy Warhol Foundation. That’s when Goldsmith discovered the series, and lodged her copyright infringement claim with the Andy Warhol Foundation. The Foundation filed suit against her for what’s known as “declaratory relief”— asking the court to declare that Warhol’s Prince images were not infringing. Goldsmith counter-sued for infringement.

The first court to deal with Goldsmith’s claims (Southern District of New York) decided that Warhol’s images were not infringing. Instead, the court held that they were “transformative” fair use. On appeal, a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit appeals court disagreed, and instead deemed them infringing. The Andy Warhol Foundation then asked for a rehearing by all thirteen of the Second Circuit judges. The full court also held that Warhol’s unauthorized 15 Prince images are infringing. As of this writing, there has been no attempt to appeal the decision to the Supreme Court (which has the discretion to turn down such a request).

This is how the Second Circuit explained the concept of “transformative”: the secondary work’s use of its source material must be “in service of a fundamentally different and new artistic purpose and character, such that the secondary work stands apart from the ‘raw material’ used to create it . . . the secondary work’s transformative purpose and character must, at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work such that the secondary work remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material.” As the court noted, in past cases involving visual artwork, collages have met this standard, because the original images were juxtaposed with other images, which resulted in new artwork that “conveys a new meaning or message separate from its source material.” See Legalities 30 Jeff Koons and Copyright Infringement.

Warhol’s Prince images, however, fell short of this standard. The district court thought that Warhol’s images had a transformative purpose because while the Goldsmith Photograph portrays Prince as “not a comfortable person” and a “vulnerable human being,” the Prince Series portrays Prince as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.” The Second Circuit rejected that rationale: “there can be no meaningful dispute that the overarching purpose and function of the two works at issue here is identical, not merely in the broad sense that they are created as works of visual art, but also in the narrow but essential sense that they are portraits of the same person.” And further, Warhol’s images duplicate specific artistic details from Goldsmith’s particular photograph, not just the generic factual appearance of Prince’s face. These include, for example, the exact angle of the shot, arrangement of Prince’s hair, his expression, the lighting on his face, and “the glint in Prince’s eyes where the umbrellas in Goldsmith’s studio reflected off his pupils.”

Those readers who are familiar with typical fair use analysis will know that there are four basic factors courts must look at to evaluate a fair use defense. The transformative issue is part of the first factor – the nature and character of the use. The other factors are: the nature of the original work, how much of it was copied, and the potential effect of such use on the copyright owner’s market for the original work.

In the first decision in this case, the district court, like many other courts that find in favor of transformative fair use, determined that the transformative nature of Warhol’s images outweighed the rest of these factors. Having decided to the contrary that Warhol’s works are not transformative, the Second Circuit analyzed the rest of the factors more thoroughly. The second and third factors weigh against fair use: the original photograph enjoys strong copyright protection, and Warhol’s images copied essentially all of its artistic expression (contrary to some common misconceptions, there is no room in this factor for considering how much of the second work is not copied from the original).

The fourth factor was the most important to their decision. Under that factor, the Second Circuit acknowledged that the market for Warhol’s artwork and Goldsmith’s photography are not in direct competition. However, the court must also consider the impact on the photographer’s market if the same sort of copying became a widespread practice. The Second Circuit found that such harm is self-evident: “There currently exists a market to license photographs of musicians, such as the Goldsmith Photograph, to serve as the basis of a stylized derivative image; permitting this use would effectively destroy that broader market, as, if artists “could use such images for free, there would be little or no reason to pay.”

The Second Circuit says, emphatically, that there is no famous artist privilege: “we feel compelled to clarify that it is entirely irrelevant to this analysis that each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol.’ Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others.”

The court found it useful to analogize the situation to that of film adaptations of novels. Famous directors, actors, and all the others who contribute to a great film have created a new and valuable work of art apart from the underlying novel. But this does not excuse them from obtaining permission from the novelist to make the film. Francis Ford Coppola could not have made The Godfather without a copyright license from Mario Puzo.

That Warhol’s images became iconic works of art doesn’t make them transformative.

Warhol created his images using photographic reproductive and silkscreen techniques that were essentially equivalent to digital copying and image manipulation techniques available to artists today. However you make it, when you start out with a mechanical reproduction of a photograph, it can be too easy to replicate features of that photograph that are protected by copyright. It is safer to draw your own artwork by hand.

Don’t assume that a photojournalist’s work is fair game just because the photographer did not stage the photo. You may remember an earlier lawsuit against Shepard Fairey claiming that his famous Obama HOPE poster infringed a photojournalist’s photograph:

Mannie Garcia’s photograph:

Shepard Fairey’s poster:

That suit settled early, when it was discovered that Fairey had lied about which photo he digitally copied for his artwork, so there was no final ruling as to whether his HOPE poster was infringing or transformative. Under the new Warhol decision, it probably would be deemed an infringement. Like Warhol’s Prince images, the purpose of the HOPE poster is the same (to depict Obama), it is based on one specific photograph, and it replicates all of the original photographer’s artistic expression, including the unusual camera angle, lighting and composition. Fairey’s stylized graphic treatment of the image is on a similar scale as Warhol’s practice of “removing certain elements from the [photograph], such as depth and contrast, and embellishing the flattened images with loud, unnatural colors,” which was not enough to make his works transformative. Nor does the fact that Fairey’s HOPE poster became a famous cultural icon make it transformative.

Visual artists should refrain from using one photograph as a reference for their own artwork. When creating a portrait, gather many different photos of your subject, and use them to create your own interpretation of that person’s features. Alter features that are unique to a particular reference photo, such as exact configuration of the person’s hair, wardrobe, or lighting. Don’t replicate a particularly unique viewpoint (such as in the HOPE poster) or distinctive glint in the subject’s eyes (like Warhol’s copy of Goldsmith’s photo).

Don’t assume that providing credit to your source photographer will escape infringement. Although Goldsmith was probably annoyed that Condé Nast failed to credit her photograph as the source of Warhol’s image, that was not the basis for the court’s finding against fair use. Fair use doesn’t mean anything that laypeople would consider “fair.” Most artists know that plagiarism is not fair. But being honest about your source image is not one of the legal fair use factors, and giving credit will not change the court’s analysis if you are sued for infringement.

If you really need to copy one specific photo, contact the photographer (or her agent) to license it explicitly for the purpose of creating an artwork based on that photo. Warhol’s original artwork for Vanity Fair was the product of such a license, and if he had simply sought an expansion of that license to cover his series of 15 additional Prince images, there would have been no infringement.

_________

You are invited to submit questions about this article, or for upcoming Legalities columns. Please send your questions to Legalities@owe.com.

LegalitiesSM is a service mark. © 2021 Linda Joy Kattwinkel. The information in this column is provided to help you become familiar with legal issues that may affect graphic artists. Legal advice must be tailored to the specific circumstances of each case, and nothing provided here should be used as a substitute for advice of legal counsel. Linda Joy is an attorney, painter and former graphic artist/illustrator. She practices intellectual property law, arts law and mediation for artists in San Francisco. She can be reached at 415-882-3200 or ljk@owe.com.